SB 1 Criminal Law - Wearing, Carrying, or Transporting Firearms - Restrictions (Gun Safety Act of 2023)

Sponsored by Senator Waldstreicher

Heard before the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee on 2/7/2023: https://www.youtube.com/live/CizgPIOuGCQ?feature=share&t=3139

MSI's Oral Testimony in Opposition

https://www.youtube.com/live/CizgPIOuGCQ?feature=share&t=8982

SB 1 as passed by the Senate being heard before the House Judiciary Committee on 3/29/2023 at 1pm.

Bruen: SB 1 is a response to the June 2022 decision of the Supreme Court in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, 142 S.Ct. 2111 (2022). Bruen holds that “the Second Amendment guarantees a general right to public carry.” 142 S.Ct. at 2135. See also Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2134 (there is a “general right to publicly carry arms for self-defense.” A “general right” to carry in public cannot be reasonably limited to particular places. Bruen explains that the “‘textual elements’ of the Second Amendment’s operative clause— ‘the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed’— ‘guarantee the individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation.’” 142 S.Ct. at 2134, quoting District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 592 (2008). The right to bear arms thus “naturally encompasses public carry” because confrontation “can surely take place outside the home.” Id.

The Bruen Court ruled that “the standard for applying the Second Amendment is as follows: When the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” 142 S.Ct. at 2127. The relevant time period for that historical analogue is 1791, when the Bill of Rights was adopted. 142 S.Ct. at 2135. That is because “‘Constitutional rights are enshrined with the scope they were understood to have when the people adopted them.’” Id., quoting District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 634–635 (2008). As stated in Hirschfeld v. Bureau of Alcohol, Firearms, Tobacco & Explosives, 5 F.4th 407, 417 (4th Cir.), vacated as moot, 14 F.4th 322 (4th Cir. 2021), cert. denied, 142 S.Ct. 1447 (2022), “[w]hen evaluating the original understanding of the Second Amendment, 1791—the year of ratification—is ‘the critical year for determining the amendment's historical meaning.” 5 F.4th at 419, quoting Moore v. Madigan, 702 F.3d 933, 935 (7th Cir. 2012) (citing McDonald, 561 U.S. at 765 & n.14). Thus, “’how the Second Amendment was interpreted from immediately after its ratification through the end of the 19th century” represented a “critical tool of constitutional interpretation.’” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2136, quoting Heller, 554 U.S. at 605. The Court stressed, however, that “to the extent later history contradicts what the text says, the text controls.” Id. at 2137. Similarly, “because post-Civil War discussions” of the right to keep and bear arms “took place 75 years after the ratification of the Second Amendment, they do not provide as much insight into its original meaning as earlier sources.’” Id., at 2137, quoting Heller, 554 U.S. at 614 (emphasis added).

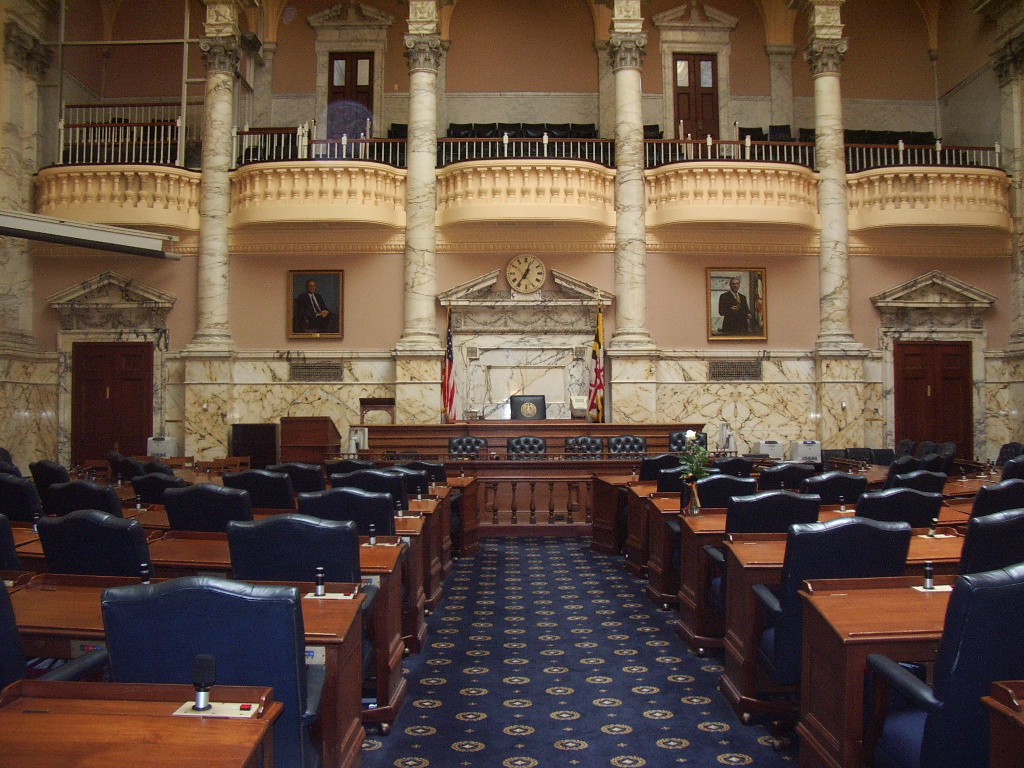

Bruen also holds that governments may regulate the public possession of firearms at five very specific locations, viz., “legislative assemblies, polling places, and courthouses,” “in” schools and “in” government buildings. Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2133, citing Heller, 554 U.S. at 599. These five all are historically justified and share the common feature that all are discrete locations that are easily identifiable. These locations are also places where armed security may be provided by the government, thus making it unnecessary for an individual to be armed for self-defense. Bruen states that “courts can use analogies to those historical regulations of ‘sensitive places’ to determine that modern regulations prohibiting the carry of firearms in new and analogous sensitive places are constitutionally permissible.” (Id.).

Again, this historical inquiry focuses on the Founding era. Thus, in Bruen, the Court rejected New York’s reliance on “a handful of late-19th-century jurisdictions,” stating these laws did not demonstrate a tradition of broadly prohibiting the public carry of commonly used firearms for self-defense.” 142 S.Ct. at 2138. The Court rejected New York’s reliance as well on other post-1791 statutory prohibitions, holding that “the history reveals a consensus that States could not ban public carry altogether.” 142 S.Ct. at 2146 (emphasis the Court’s).

The State is not free to enact “sensitive area” legislation that that “would in effect exempt cities from the Second Amendment” because such laws “would eviscerate the general right to publicly carry arms for self-defense.” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2134. For the same reason, the Bruen Court specifically rejected New York’s assertion that sensitive places “include ‘all “places where people typically congregate and where law-enforcement and other public-safety professionals are presumptively available.’” Id. at 2133, quoting New York’s brief. As the Court explained, “expanding the category of ‘sensitive places’ simply to all places of public congregation that are not isolated from law enforcement defines the category of “sensitive places” far too broadly.” Id. at 2134 (emphasis added). See Siegel v. Platkin, 2023 WL 1103676 (D.N.J. Jan. 30, 2023) *12 (holding that “‘sensitive place’ is a term within the Second Amendment context that should not be defined expansively”).

For the reasons explained below, if enacted into law, SB 1 would likely be “dead on arrival” in federal court as it was plainly intended to restrict the very “general right” to carry in public that Bruen expressly holds that the State must allow under the Second Amendment. As Congressman Raskin recently stated in the context of a carry bill enacted by Montgomery County, “there is no reason for us to be passing ordinances that we know that will be struck down.” https://youtu.be/TrM4_JVlURs?t=733 (at 13:56).

SB 1, as passed by the Senate:

SB 1, as passed by the Senate, creates multiple new places in which firearms are banned. In new section 4-111, SB 1 bans firearms in 3 areas and then defines each of the three. The three are 1. "Area for children and vulnerable individuals" 2. A "special purpose area," and 3. “government or public infrastructure area.” SB 1 also creates a new Section 6-411, which addresses other private property areas, banning firearms in dwellings without permission of the owner or lessee and allowing private property owners to post GFZ signs and giving those signs the force of law. This structure suffers from numerous flaws.

Special Purpose Areas: The definition of “Special Purpose Area” is far too broad. It is defined by SB 1 as:

(I) A location licensed to sell or dispense alcohol or cannabis for on–site consumption;

(II) A stadium;

(III) A museum;

(IV) A location being used for:

- An organized sporting or athletic activity (except for shooting sports);

- A live theater performance;

- A musical concert or performance for which members of the audience are required to pay or possess a ticket to be admitted; OR

- A fair or carnival;

(V) A racetrack;

(VI) A video lottery facility, as defined in § 9–1A–01 of the State Government Article, OR

(VII) Within 100 yards of a place where a public gathering, a demonstration, or an event which requires a permit from the local governing body is being held, if signs posted by a law enforcement agency conspicuously and reasonably inform members of the public that the wearing, carrying, and transporting of firearms is prohibited.

No signage is required for any of these three areas. Firearms are flatly banned, unless the possession is by a person who is otherwise excepted under Section 4-111(b).

None of these above places have a proper “longstanding” and “well-established, representative, historical analogue” from 1791, as required by Bruen. See Bruen,142 S.Ct. 2133. The sole common denominator for all these locations is that they are places at which people may assemble in public. As such, these places run head long into Bruen’s holding that places where people “congregate” or assemble simply are not “sensitive places.” Id. Certainly, none of these places are remotely analogous to the five discrete sensitive places identified in Bruen. These places do not involve children (schools), the need to protect government officials (government buildings, legislative assemblies, and courthouses) or the political process (polling stations). Nor can these places be justified for other reasons. Bruen made clear that the analogue inquiry is controlled by reference to two “metrics” which are “how and why the regulations burden a law-abiding citizen's right to armed self-defense.” Id. Here, there is no historical tradition dating back to 1791 that disarmed law-abiding persons in these locations. Quite to the contrary. See D. Kopel & J. Greenlee, The “Sensitive Places” Doctrine, 13 Charleston L. Rev. 205, 229–236, 244–247 (2018), cited with approval in Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2133. The absence of any such regulation is largely dispositive. See Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2131 (“the lack of a distinctly similar historical regulation addressing that problem is relevant evidence that the challenged regulation is inconsistent with the Second Amendment”).

Particularly egregious in its practical effects is the ban on firearms in locations licensed to sell alcohol for on-site consumption. That ban would include almost all restaurants in the State, other than fast food outlets, such McDonald’s and Wendy’s. It would ban the mere entry into the restaurant, even for a carryout, regardless of whether the permit holder consumes any alcohol or is even goes into the bar section of the restaurant. Respectfully, that is absurd. People need to eat. This prohibition will force permit holders to stow their firearms in their vehicles, where they are open to theft, whenever they go inside a restaurant. Indeed, this ban could extend to hotels, as many hotels have bars, and the hotel (not merely the bar) is the “location licensed” to sell alcohol for on-site consumption. It is insane to pass a bill that will require permit holders to store their guns in their parked cars while they eat or sleep. Theft from vehicles is a growing serious problem, as the New York Times has recently documented. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/25/us/illegal-guns-parked-cars.html.

Similarly absurd is the ban on possession in any “video lottery facility.” As that term is defined by Section 9-1A-01(aa) (incorporated by reference by SB 1), this ban would include not only actual casinos (of which there are four in this State), but also include “a facility at which players play video lottery terminals and table games under this subtitle.” Such terminals are widely distributed in the State, including at 7-11s, Royal Farms gas station/marts and a variety of ordinary corner markets. A person who goes inside to pay for gas, use the restroom or buy a sandwich or a snack becomes a criminal the moment she walks inside the door to do so. Indeed, because the term “facility” is not defined, she may even be arrested and prosecuted for gassing up at the pumps without ever entering the interior of the mart. At the very least, this restriction should be limited to actual casinos, not every video lottery facility.

Areas for Children and Vulnerable Individuals: As noted, Section 4-111, as added by SB 1, bars all firearms, including by permit holders, in any “Area for Children and Vulnerable Individuals,” including in “a health care facility, as defined in § 15–10b–01 of the Insurance Article.” Section 15-10b-01, in turn defines that term to mean:

(1) a hospital as defined in § 19-301 of the Health-General Article;

(2) a related institution as defined in § 19-301 of the Health-General Article [which includes overnight personal or nursing care for 2 or more individuals]

(3) an ambulatory surgical facility or center which is any entity or part thereof that operates primarily for the purpose of providing surgical services to patients not requiring hospitalization and seeks reimbursement from third party payors as an ambulatory surgical facility or center;

(4) a facility that is organized primarily to help in the rehabilitation of disabled individuals;

(5) a home health agency as defined in § 19-401 of the Health-General Article;

(6) a hospice as defined in § 19-901 of the Health-General Article;

(7) a facility that provides radiological or other diagnostic imagery services;

(8) a medical laboratory as defined in § 17-201 of the Health-General Article; or

(9) an alcohol abuse and drug abuse treatment program as defined in § 8-403 of the Health-General Article.

These locations suffer from the same flaw as the “special purpose areas” as none are supported by any well-established, representative historical analogue. The rationale appears to be that these locations house “vulnerable” individuals.” But such a rationale plainly fails because there is no historical analogue that disarmed people because of that reason. As Bruen holds, the controlling inquiry is “how and why” the historical regulation affected the right of self-defense. If anything, vulnerable people have an increased need for arming themselves, not a diminished need. There is no long-standing or enduring American historical tradition of forcing vulnerable people to disarm. The very notion is senseless.

An ordinary law-abiding person is also unlikely to understand these definitions, as the definitions rely on multiple levels of cross-referenced Maryland Code provisions. There is no signage requirement. Some of these locations are obvious, like a hospital, but many are not. A permit holder who enters any one of these facilities can do jail time without ever receiving notice or an opportunity for compliance. For example, there is no definition for a facility that is organized “primarily” to help the rehabilitation of disabled persons. Does that definition include gyms at which rehabilitation takes place? How would any permit holder possibly know whether a given facility is organized “primarily” for these purposes?

The definition of a “home health agency” is even further afield. The referenced definition, found in § 19-401(b) of the Health-General Article, defines the term to mean “a health-related institution, organization, or a part of an institution that:

(1) Is owned or operated by 1 or more persons, whether or not for profit and whether as a public or private enterprise; and

(2) Directly or through a contractual arrangement, provides to a sick or disabled individual in the residence of that individual skilled nursing services, home health aid services, and at least one other home health care service that are centrally administered.

So, does the ban on firearms apply to the “residence” of the “sick or disabled” person who is receiving services? Or does the ban apply to the “other home health service” location which “centrally administers” the service? Or does it apply only to the office of the organization or institution or agency that provides such home care services? And if it is only the latter, what possible justification is there for treating such offices or locations any differently than any other office? The services to the “vulnerable” persons are rendered at the residence of the individual, not at the office building of the organization.

A medical laboratory, as defined by the referenced section of the Health-General article of the Maryland Code includes “any facility, entity, or site that offers or performs tests or examinations in connection with the diagnosis and control of human diseases or the assessment of human health, nutritional, or medical conditions or in connection with job-related drug and alcohol testing.” MD Code, Health-General, § 17-201(c)(1). That definition does not give reasonable notice. A facility that provides offers or performs “tests or examinations” could easily be read to include a private doctor’s office, or even the neighborhood CVS pharmacy. A permit holder simply has no way of knowing whether such tests or examinations are performed at any given location. A permit holder who enters the CVS pharmacy to buy school supplies or a gallon of milk will be subject to arrest.

Similarly, a facility that “provides radiological or other diagnostic services” could include any private doctor’s or dentist’s office with an x-ray machine. The term “diagnostic services” is utterly undefined. But even if the term was clear, a permit holder could go to jail regardless of whether she even knew of the existing of such devices or services at the location and regardless of whether such tests services were used on the individual. All these difficulties illustrate the problems associated with using existing definitions, which were enacted for entirely different civil regulatory purposes, and applying such definitions to impose criminally enforceable firearms restrictions. Such short-hand definitions are simply too vague to be criminally enforceable under the Due Process Clause

Government Or Public Infrastructure Areas: Section 4-111, as created by SB 1, also bans carry in “Government Or Public Infrastructure Area,” which is defined as:

(I) A building owned or leased by a unit of State or local government;

(II) A building of a public or private institution of higher education, as defined in § 10–101 of the Education Article;

(III) A location that is currently being used as a polling place in accordance with title 10 of the Election Law Article or for canvassing ballots in accordance with title 11 of the Election Law Article; or

(IV) an electric plant or electric storage facility, as defined in § 1–101 of the Public Utilities Article.

A “government building” can be a sensitive place as noted in Bruen. Likewise, Bruen permits bans in polling places. But there are multiple issues with how “government building” is defined as well as with remaining areas banned under this part of SB 1.

First, there is no signage required for a government building so, apart from obvious cases, there is no practical way for someone to know whether a given building is government “owned or leased.” In contrast, federal law, 18 U.S.C. § 930, expressly requires signage (or actual knowledge) before a person may be convicted of carrying a firearm into a federal facility under that provision. That sign looks like this:

SB 1 is a criminal statute. The State should be seeking to foster compliance rather than imposing criminal sanctions for innocent mistakes. It is not asking too much for government buildings be signed in a similar manner. All it would take is a decal on the door.

Moreover, unlike “government buildings” as used in SB 1, a “federal facility” under Section 930 is a defined term and the definition is whether federal employees are “regularly” located in the building. Ownership or a leasehold is not controlling or even relevant. Under SB 1 a building leased by a local government is covered even though it has no government employees and even though it could be used for proprietary purposes, rather than government purposes. A government building that is being used for propriety or non-governmental purposes is not a “government building” within the meaning Bruen. Such buildings are improperly designated gun free zones.

Second, there is no well-established, representative 1791 historical analogue for banning guns at higher education institutions for all adults (other than students), particularly at private institutions of higher education. Such private institutions have historically provided their own policies. Indeed, Section 6-411, as created by SB 1, would permit private colleges to post GFZ signs however they like. The State simply may not substitute its judgment for that of private property owners. See Siegel, 2023 WL 1103676 at *16-*17.

Likewise, there is no historical analogue for banning firearms at an electric plant, which, of course, did not exist in 1791. The term “electric plant” is defined at the reference Code provision to mean “the material, equipment, and property owned by an electric company and used or to be used for or in connection with electric service” MD Code, Public Utilities, § 1-101(j). That definition could include a simple, privately owned warehouse that stored “equipment” that could be used “in connection with electric service”. A warehouse is not a sensitive location in any sense, much less an historically justified sensitive place. Without a signage requirement, no permit holder would have notice that such locations are being used for the storage of equipment that could “be used for or in connection with electric service.” We know of no historical analogue for such a place. Under Bruen, the burden is on the State to prove an historical analogue for disarming people in “infrastructure” areas. Again, any such analogue must be justified by reference to the Court’s “how and why” metrics. Any other policy reasons for doing so are simply irrelevant.

LEOSA: Section 4-111(b) sets forth exceptions and exemptions from the regulatory bans imposed by that section. Specifically, Section 4-111(b)(1) provides an exception from Section 4-111 for “a law enforcement official of the United States, the state, or a local law enforcement agency of the state.” Section 4-11(b)(7) contains another exception, providing an exception for:

Subject to subsection (i) of this section, an off–duty law enforcement official or a person who has retired as a law enforcement official in good standing from a law enforcement agency of the United States, the State, or a local unit in the State who possesses a firearm, if:

(i) 1. the official or person is displaying the official’s or person’s badge or credential;

- the firearm carried or possessed by the official or person is concealed from view under or within an article of the official’s or person’s clothing; and

- the official or person is authorized to carry a handgun under the laws of the state or the United States; or

(ii) 1. the official or person possesses a valid permit to wear, carry, or transport a handgun issued under title 5, subtitle 3 of the Public Safety Article; and

- the firearm carried or possessed by the official or person is concealed from view under or within an article of the official’s or person’s clothing;

These provisions are preempted by the Law Enforcement Office Safety Act (“LEOSA”), Pub. L. 108–277, 118 Stat. 865 (2004), codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. § 926B and 18 U.S.C. § 926C. Those federal law provisions allow an active-duty law enforcement officer (“LEO”) of any federal agency or of any state or local agency, nationwide (§ 926B), and a retired LEO of any federal agency or any state or local agency, nationwide (§ 926C) to carry concealed "[n]otwithstanding any other provision of the law of any State or any political subdivision.”

Specifically, the exception provided in Section 4-111(b)(1) for active-duty LEOs is limited to federal LEOs and LEOs employed by Maryland State agencies and localities. Section 4-111(b)(1) does not include active-duty LEOs of other States. In contrast, Section 926B expressly encompasses all active-duty LEOs of any State or federal agency, nationwide. Second, Section 4-111(b)(4) expressly excepts an active-duty LEO of another state only if he or she is in Maryland on “official business.” The nationwide carry rights accorded by Section 926B to all LEOs are not so limited. Third, Section 4-111(b)(7) requires the off-duty LEO or retired LEO to display his or her “badge or credential.” Under Sections 926B and 926C, the LEO or retired LEO need only “carry” his credentials, not display them. Fourth, Section 4-111(b)(7)(ii), provides that the LEO or retired LEO need not display his or her badge or credentials if he or she has a Maryland wear and carry permit. No such provision or limitation is found in Sections 926B or 926C. These LEOSA provisions are judicially enforceable, as New Jersey recently discovered when its restrictions on LEOSA carry rights were struck down in Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association v. Grewal, 2022 WL 2236351 (D.N.J. June 21, 2022), appeal pending No. 22-2209 (3d Cir.). Unless SB 1 is amended, the restrictions on LEOSA rights imposed by SB 1 will meet the same fate. MSI has numerous members who carry under LEOSA.

Conflict with Section 4-203: New Section 4-111 provides for penalties for carry by a permit holder in banned areas of 90 days for the first offense and 15 months for a second or subsequent offenses. See 4-111(g). Section 6-411(d) imposes a similar set of penalties for a violation of Section 6-411 (addressing carry within a dwelling or on posted private property), with a term of imprisonment of 90 days for the first offense and 6 months for the second and subsequent offenses. While substantial, these penalties do not create a firearms disqualification and appropriately so, given that the offenses apply, as practicable matter, solely to permit holders and the violation may well have been inadvertent.

However, these penalties are incompatible with the penalties imposed by Section 4-203 of the Criminal Law Article. As amended in 2013, Section 4-203(b)(2) exempts permit holders from the general ban on carry otherwise imposed by Section 4-203(a), but limits that exemption to “the wearing, carrying, or transporting of a handgun, in compliance with any limitations imposed under § 5-307 of the Public Safety Article, by a person to whom a permit to wear, carry, or transport the handgun has been issued under Title 5, Subtitle 3 of the Public Safety Article.” (Emphasis added).

On the back of every carry permit, the State Police have placed a Section 307 limitation stating: “Not valid where firearms are prohibited by law.” Thus, if a permit holder carries in any location in which firearms are banned by SB 1, even by mistake or inadvertence, the permit is NOT VALID. Without a “valid” permit, a permit holder who carries, by mistake or otherwise, in such banned locations may be charged under Section 4-203, which imposes a 3-year term of imprisonment. A conviction under Section 4-203 is disqualifying under Maryland law and federal law. See MD Code, Public Safety, 5-101(g)(3) (defining a disqualifying crime to include any crime punishable by more than 2 years in prison); 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1); 18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(20) (imposing a lifetime federal disqualification for any State misdemeanor conviction punishable by more than 2 years). Section 4-203(a)(1)(i) has no mens rea requirement. Maryland’s highest court has thus held that Section 4-203(a)(1)(i) is a strict liability statute, and thus imposes criminal liability regardless of whether the violation was knowing or willful. Lawrence v. State, 475 Md. 384, 408, 257 A.3d 588, 602 (2021). Likewise, nothing in Section 4-111 or Section 6-411 requires a knowing or willful violation.

Basically, inadvertent carry into any one of the many, unsigned gun-free-zones established by SB 1 would make the permit holder criminally liable under both Section 4-203 and under lesser penalties established by Section 4-111(g) and Section 6-411(d), thus effectively rendering Section 4-111(g) and Section 6-411(d) irrelevant as a mere lesser included offense. See State v. Prue, 414 Md. 531, 996 A.2d 367, 378 (2010). That result is particularly egregious as the impact of that reality would fall solely on permit holders, as non-permit holders generally may not carry in public at all under Section 4-203(a). Permit holders are, of course, thoroughly vetted by the State Police and are quite likely to the most law-abiding persons in the State. There is no conceivable justification for severely punishing permit holders for mistakes or inadvertence.

Application of Section 4-203 to permit holders for carrying in areas newly banned by SB 1 would obviously be contrary to legislative intent. As passed by the Senate, SB 1 was intended to impose a different set of penalties for persons who have carry permits. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/FloorActions/Media/senate-41-A?year=2023RS (on third reader, remarks of Senator Waldstreicher starting at 1:00) (making this point). See also https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/FloorActions/Media/senate-40-?year=2023RS (on second reader, remarks of Senator Waldstreicher starting at 2:00, noting that SB 1 was not intended to “jam anyone up”).

To avoid this unintentional nullification of the penalty provisions of Section 4-111(g) and Section 6-411(d), SB 1 must be amended to provide that the Bill's punishments in Section 4-111(g) and Section 6-411(d) for any violation of Section 4-111 and Section 6-411 apply to permit holders in lieu of any penalty imposed by Section 4-203. Such an amendment is easily done simply by inserting into Section 4-111(g) and Section 6-411(d), a clause stating: “Notwithstanding Section 4-203 of the Criminal Law Article, a violation of Section 4-111 [or 6-411] by a person to whom a permit to wear, carry, or transport the handgun has been issued under Title 5, Subtitle 3 of the Public Safety Article, is guilty of a misdemeanor and on conviction is subject to:” at the beginning of Section 4-111(g) and Section 6-411(d). See, e.g, McGraw v. Loyola Ford, 124 Md.App. 560, 723 A.2d 502, 518 (1999) (explaining the meaning of a “notwithstanding” clause).

.

Any Desire To Curtail Bruen Is Constitutionally Illegitimate: A government may not suppress possible adverse secondary effects flowing from the exercise of a constitutional right by suppressing the right itself. See, e.g., City of L.A. v. Alameda Books, Inc., 535 U.S. 425, 449-50 (2002) (Kennedy, J., concurring) (“It is no trick to reduce secondary effects by reducing speech or its audience; but [the government] may not attack secondary effects indirectly by attacking speech”). See Imaginary Images, Inc. v. Evans, 612 F.3d 736, 742 (4th Cir. 2010) (same); St. Michael’s Media, Inc. v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 566 F.Supp.3d 327, 374 (D. Md. 2021), aff’d., 2021 WL 6502219 (4th Cir. 2021) (same). This point applies to Second Amendment rights no less than to other constitutional rights. Grace v. District of Columbia, 187 F.Supp.3d, 124, 187 (D.D.C. 2016), aff’d, sub. nom. Wrenn v. Dist. of Columbia, 864 F.3d 650 (D.C. Cir. 2017) (“it is not a permissible strategy to reduce the alleged negative effects of a constitutionally protected right by simply reducing the number of people exercising the right”) (quotation marks omitted). See Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2126, 2148 (citing Wrenn with approval). “[T]he enshrinement of constitutional rights necessarily takes certain policy choices off the table.” Heller, 554 U.S. at 636. As the Supreme Court noted in Bruen, “[t]he constitutional right to bear arms in public for self-defense is not ‘a second-class right, subject to an entirely different body of rules than the other Bill of Rights guarantees.’” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2156 (citation omitted).

The Senate leadership has suggested that the exercise of Second Amendment rights by permit holders under Bruen is outweighed by the fears or discomforts the non-permit holding members of public may have that a permit holder may be carrying a concealed firearm nearby. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wx0ZJm69X7E&t=1599s starting at minute 28.00. However, legislation based on that notion is constitutionally illegitimate. Any law enacted for the avowed purpose of minimizing or curtailing the exercise of a constitutional right is “patently unconstitutional.” See Saenz v. Roe, 526 U.S. 489, 499 n.11 (1999) (“[i]f a law has ‘no other purpose . . . than to chill the assertion of constitutional rights by penalizing those who choose to exercise them, then it [is] patently unconstitutional.’”), quoting United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570, 581 (1968) (brackets and ellipsis the Court’s).

Fundamentally, unpopular constitutional rights may not be suppressed merely because their exercise might cause discomfort in others. Kenney v. Bremerton School District, 142 S.Ct. 2407, 2427-28 (2022) (rejecting a “heckler’s veto”). See also Forsyth Cnty. v. Nationalist Movement, 505 U.S. 123, 134-35 (1992) (“Speech cannot be ... punished ... simply because it might offend a hostile mob.”). Bruen abrogated “means-end,” interest-balancing under which such concerns might have been relevant and made clear that “[t]he constitutional right to bear arms in public for self-defense is not ‘a second-class right, subject to an entirely different body of rules than the other Bill of Rights guarantees.’” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2156 (citation omitted). See Koons, slip op. at *9 (“a balancing of interests” is something “this Court cannot do” under Bruen).

It is no answer to Bruen to emotionally assert that guns are not the answer to violent crime. That argument simply is incompatible with Bruen’s holding that there is “general right” to carry in public. Law-abiding residents of Maryland are rushing to obtain carry permits after Bruen because Maryland, with all its highly restrictive gun-control laws and policies, has been singularly unsuccessful in controlling violent crime, particularly in urban areas. Bruen confirms that law-abiding people have a constitutional right to obtain carry permits on a “shall issue” basis so that they may defend themselves in public with firearms. As the segregationists discovered in the 1950s and 1960 when they refused to accept Brown v. Board of Education, defying the Supreme Court ultimately fails. It also results in massive attorneys’ fees awards against the State and local governmental defendants under 42 U.S.C. § 1988. For example, the attorneys for plaintiffs in Bruen have sought a fee award of $1,269,232.13. And that litigation proceeded very quickly. More importantly, restricting the right to carry and imposing still more gun control restrictions will not make people feel safer. People feel less safe when they cannot defend themselves, which is why otherwise law-abiding people carry in Baltimore.

Insanity is commonly defined as “doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” SB 1 fits that definition. The General Assembly should stop focusing on inanimate objects and illegally restricting the rights of law-abiding citizens and start insisting on accountability from State government agencies and local government officials who are in the position to enforce existing laws that bar disqualified persons from possessing and carrying firearms. Persons who use firearms for criminal purposes must be arrested and prosecuted and thus individually held accountable. Maryland fails miserably on that score.

This testimony reflects SB 1 as it was introduced and SB 118, which was withdrawn by Senator Waldstreicher:

SB 1: SB 1 provides that “A PERSON MAY NOT KNOWINGLY WEAR, CARRY, OR TRANSPORT A FIREARM ONTO THE REAL PROPERTY OF ANOTHER UNLESS THE OTHER HAS GIVEN PERMISSION, GENERALLY, EXPRESS EITHER TO THE PERSON OR TO THE PUBLIC TO WEAR, CARRY, PROPERTY. OR TRANSPORT A FIREARM ON THE REAL PROPERTY.” A violation of this provision is punishable by imprisonment up to 1 year.

SB 1 also provides “A PERSON MAY NOT KNOWINGLY WEAR, CARRY, OR TRANSPORT AFIREARM WITHIN 100 FEET OF A PLACE OF PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION.” A violation of this provision is likewise punishable by imprisonment by up to 1 year. The Bill does not allow for any exceptions to this ban. As written, the ban applies to the owners and operators of every such “place of public accommodation.” Such owners are not allowed to give permission to anyone.

For purposes of this provision, a “place of public accommodation” is defined by reference to the meaning of that term set forth in MD Code, State Government, § 20-301, which very broadly defines the term to mean any place that “provides lodging to transient guests,” any “restaurant” or similar location that sells “food or alcohol” for consumption “on or off the premises,” any “retail establishment” that is operated by any “private or public entity” and “offers goods, services, entertainment, recreation or transportation.”

SB 118: SB 118 provides that “A PERSON MAY NOT KNOWINGLY WEAR, CARRY, OR TRANSPORT A FIREARM ON PRIVATE PROPERTY OWNED BY ANOTHER UNLESS:

(1) THE OWNER OF THE PROPERTY HAS GIVEN THE PERSON EXPRESS PERMISSION TO WEAR, CARRY, OR TRANSPORT THE FIREARM ON THE PROPERTY, OR

(2) THE OWNER OF THE PROPERTY HAS POSTED A CLEAR AND CONSPICUOUS SIGN INDICATING THAT IT IS PERMISSIBLE TO WEAR, CARRY, OR TRANSPORT A FIREARM ON THE PROPERTY.”

In a separate section, SB 118 provides that “A PERSON MAY NOT KNOWINGLY WEAR, CARRY, OR TRANSPORT A FIREARM IN OR ON PROPERTY CONTROLLED BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT, THE STATE GOVERNMENT, OR A LOCAL GOVERNMENT.” SB 118 creates a “REBUTTABLE PRESUMPTION” that any violation of its provisions is done “knowingly.” A violation of these provisions is punishable by up to 2 years in prison and a $5,000 fine.

Introduction And The Current State of the Law: These Bills are in response to the June 2022 decision of the Supreme Court in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, 142 S.Ct. 2111 (2022), where the Court struck down as unconstitutional New York’s “proper cause” requirement for issuance of a permit to carry a handgun in public. That holding effectively abrogated Maryland’s “good and substantial reason” requirement for permits, found in MD Code, Public Safety, 5-306(a)(6)(ii), as there is not a scintilla’s worth of difference between New York’s “proper cause” requirement and Maryland’s “good and substantial reason” requirement. As a result, the Maryland Attorney General and the Governor instructed the State Police that the “good and substantial reason” requirement could no longer be enforced. https://bit.ly/3UraHuB. The Maryland Court of Special Appeals agreed. Matter of Rounds, 255 Md.App. 205, 213, 279 A.3d 1048 (2022) (“We conclude that this ruling [in Bruen] requires we now hold Maryland’s ‘good and substantial reason’ requirement unconstitutional.”). Maryland wear and carry permits are thus now issued on a “shall issue” basis to all applicants who otherwise satisfy the stringent training, fingerprinting and background investigation requirements otherwise set forth in MD Code, Public Safety, § 5-306(a)(5),(6). The General Assembly should thus repeal the “good and substantial reason” requirement. Neither of these Bills purport to do so.

Bruen holds that “the Second Amendment guarantees a general right to public carry.” 142 S.Ct. at 2135. See also Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2156 (“The Second Amendment guaranteed to ‘all Americans’ the right to bear commonly used arms in public subject to certain reasonable, well-defined restrictions.”); id., at 2134 (there is a “general right to publicly carry arms for self-defense.” A “general right” to carry in public cannot be reasonably limited to particular places. Bruen explains that the “‘textual elements’ of the Second Amendment’s operative clause— ‘the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed’— ‘guarantee the individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation.’” 142 S.Ct. at 2134, quoting District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 592 (2008). The right to bear arms thus “naturally encompasses public carry” because confrontation “can surely take place outside the home.” Id. The text of the Second Amendment is thus informed by the right of self-defense. No one can dispute that Bruen recognizes that the right of self-defense extends outside the home. See also United States v. Rahimi, --- F.4th ----, 2023 WL 1459240, slip op. at 12 (5th Cir. Feb. 2, 2023).

For the reasons explained below, if enacted into law, these extreme Bills (SB 1 and SB 118) would be “dead on arrival” in federal court as these bills are plainly intended to ban the very “general right” to carry in public that Bruen expressly holds that the State must allow under the Second Amendment. As Congressman Raskin recently stated in the context of a carry bill enacted by Montgomery County, “there is no reason for us to be passing ordinances that we know that will be struck down.” https://youtu.be/TrM4_JVlURs?t=733 (at 13:56).

The Bills are extreme. Both Bills ban the possession of any firearm on the private or real property of “another” unless given permission by the owner, either via express permission (SB 1) or via signage (SB 118). Yet even such permission would be insufficient at or within 100 feet of any place of “public accommodation,” where the ban would be total. SB 118 (unlike SB 1) also broadly bans possession of any firearm, without exception, ‘in or on property controlled” by any governmental entity. Both Bills are unprecedented in American law. Bruen holds that a State may not enact legislation that “would in effect exempt cities from the Second Amendment” because such laws “would eviscerate the general right to publicly carry arms for self-defense.” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2134. The Court thus stated “there is no historical basis for New York to effectively declare the island of Manhattan a “sensitive place” simply because it is crowded and protected generally by the New York City Police Department.” Id. Taken together, the Bills would effectively “eviscerate” the right to carry in cities and throughout much of Maryland. Maryland’s urban areas are no more “sensitive” than Manhattan.

Indeed, it is hard to think of a single location in urban Maryland at which firearms would not be banned as the Bills, taken together would ban possession on all private property open to the public and on all government-controlled property, regardless of whether a person had a wear and carry permit. Carry on private property is presumptively banned. SB 118 bans carry in or on any government “controlled” property. What’s left? Indeed, these Bills would quite literally ban all firearms by any person at the store of a federally licensed or state licensed firearms dealer and thus force the closure of every such dealer. The Bill would also literally prevent every business owner from carrying a firearm in his own business if it was open to the public. Yet, such business possession is currently allowed, without a carry permit, by MD Code, Criminal Law, §§ 4-203(b)(6) and 4-203(b)(7). By banning all firearms on or in all property controlled by any government, the Bills would literally ban hunting on all public lands and mandate the closure of firing ranges currently maintained by the Department of Natural Resources. The Bill would thus devastate economies of rural areas of the State that rely on hunting and deprive owners of much-need access to public ranges where skills can be honed and practiced. This ban on possession on government-controlled property would preclude the mere possession of firearms in locked containers and being shipped at airports in accordance with TSA regulations. 49 C.F.R. § 1540.111(c), 1544.203(f). One must seriously question whether any thought given to these realities in crafting the Bill.

A word on penalties. SB 1 punishes violations by up to one year of imprisonment. The punishment for a violation of SB 118 is up to (but not exceeding) 2 years imprisonment. Neither punishment creates a disqualification for the possession of firearms. See MD Code, Public Safety, § 5-101(g) (defining disqualifying crime as a misdemeanor punishable by more than 2 years imprisonment); 18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(20) (same). But, for permit holders (and for everyone with respect to handguns), the penalty is likely to be much higher. That is because nothing in these Bills amends the broad ban on the wear, carry and transport of handguns imposed by MD Code, Criminal Law, § 4-203(a), subject to specific exceptions in subsection 4-203(b). Pursuant to the authority granted by MD Code, Public Safety, § 5-307, the State Police have placed a restriction on every permit providing that the permit is “not valid where firearms are prohibited by law.” That means every “sensitive place” ban on firearms imposed by the State, by an agency regulation or by a locality invalidates a permit at that location and makes the permit holder open to prosecution under MD Code, Public Safety, 4-203(a), a violation of which is punishable by up to 3 years imprisonment for the first offense. Section 4-203(a) is a strict liability criminal statute, and thus does not require the State to satisfy any mens rea requirement. See Lawrence v. State, 475 Md. 384, 257 A.3d 588 (2021). A conviction under Section 4-203(a) results in a life-time firearms disqualification under State and federal law. A simple mistaken entry into a “sensitive place” can thus have draconian consequences for a permit holder. Indeed, broad “sensitive area” restrictions would effectively ban all firearms in places where persons are specifically allowed to wear, carry and transport handguns, such in businesses and other locations specified in subsection 4-203(b). State-issued permits should thus be narrow, well-defined and governed by very clear State-wide rules and regulations.

Highly restrictive “sensitive place” laws were enacted after the decision in Bruen by New York and New Jersey. Those bans were promptly enjoined by the federal courts, including by separate federal district courts in New York and by the federal district court for the District of New Jersey. See Koons v. Reynolds, --- F.Supp.3d ----2023 WL 128882 (D.N.J. Jan. 9, 2023) (granting a temporary restraining order); Siegel v. Platkin, 2023 WL 1103676 (D.N.J. Jan. 30, 2023) (same); Antonyuk v. Hochul, --- F.Supp.3d ---, 2022 WL 16744700 (N.D.N.Y. Nov. 7, 2022) (granting a preliminary injunction) and Christian v. Nigrelli, --- F.Supp.3d ---, 2022 WL 17100631 (W.D.N.Y. Nov. 22, 2022) (same). In Hardaway v. Nigrelli, --- F.Supp.3d ---, 2022 WL 16646220 (W.D.N.Y. Nov. 3, 2022) (preliminary injunction), and Hardaway v. Nigrelli, --- F.Supp.3d ---, 2022 WL 11669872 (W.D.N.Y. Oct. 20, 2022) (TRO), the court enjoined that part of the New York statute that banned possession in houses of worship. That holding was followed in Spencer v. Nigreilli, 2022 WL 17985966 (W.D.N.Y. Dec. 29, 2022) (preliminary injunction).

Particularly instructive for purposes of these Bills are the decisions in Antonyuk, Christian, Siegel and Koons. Antonyuk and Christian held that New York may not constitutionally establish a “default rule” that would presumptively ban carry on private property without the owner’s express permission. That is precisely the sort of ban imposed by these Bills. The court in Antonyuk ruled that New York’s attempt to impose such a presumptive ban on all carry on private property “appears to be a thinly disguised version of the sort of impermissible “sensitive location” regulation that the Supreme Court considered and rejected in NYSRPA.” 2022 WL 16744700 at *81. That court found no historically appropriate analogue for such a ban. Id. at *80. Likewise in Christian, the court held that historically “carrying on private property” was “generally permitted absent the owner's prohibition,” 2022 WL 17100631 at *9, and that the right to exclude persons from private property “has always been one belonging to the private property owner—not to the State.” Id. (emphasis the court’s). The Christian court thus concluded New York’s “current policy preference” for such a presumptive ban “is one that, because of the interest balancing already struck by the people and enshrined in the Second Amendment, is no longer on the table.” Id., citing Heller, 554 U.S. at 636, and Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2131.

Similarly, in Koons, the New Jersey federal district court granted a TRO to enjoin New Jersey’s presumptive ban with respect to carry on private property, stating that the New Jersey defendants “seem to turn a private property owner's lack of consent and/or right to exclude into a general proposition that the Second Amendment does not presume the right to bear arms on private property. Nothing in the text of the Second Amendment draws that distinction.” 2023 WL 128882 at *16. As the court explained, “the State is, in essence, criminalizing the conduct that the Bruen Court articulated as a core civil right.” Id. In Siegel, the court enjoined New Jersey bans on the carrying of firearms in parks, beaches, recreational facilities, public libraries, museums, bars, restaurants, where alcohol is served, entertainment facilities, in vehicles and on private property without the prior permission of the owner. In each instance, the court found that “the Second Amendment’s plain text covers the conduct in question (carrying a concealed handgun for self-defense in public).” Slip op. at 23, 29, 30, 31, 32, 46 (emphasis added). In so holding the court relied on the very “textual elements” identified in Bruen, viz., the right to be armed “‘in a case of conflict with another person,’” noting that “this definition naturally encompasses one’s right to public carry on another’s property, unless the owner says otherwise.” Id. at 38. The same analysis applies, a fortiori, to the possession and carry on public property, such as on a public sidewalk or in other public places where confrontation can and does take place.

These holdings are consistent with and, indeed, mandated by Bruen’s holding that there is a general right to carry in public, subject to narrowly confined restrictions. Indeed, the bans imposed by these Bills are even more extreme than imposed by New York and New Jersey. For example, under the New York law, shop owners had the option of allowing carry by permit holders at their places of business, either by signage or by express permission. See Christian, 2022 WL 17100631 at *1. The same is true under the New Jersey statute at issue in Koons and Siegel Koons, 2023 WL 128882 at *2. In contrast, SB 1 bans all carry at any place of “public accommodation” (a term that includes every retail store or location open to the public), regardless of whether permission is granted. Bill SB 1 thus does not merely establish a presumptive ban on carry at such private property, it totally bans such carry without regard to the private owner’s preferences. The statutes at issue in New York are New Jersey are already extreme, but neither State sought to go that far. Maryland would be the first and only State to impose that restriction on the general right to carry articulated in Bruen.

New York has appealed the preliminary injunctions issued in these cases to the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. That court has stayed these preliminary injunctions pending appeal and ordered expedited briefing and argument. However, that stay order expressly exempts from the stay that part of the any preliminary injunction that enjoined the New York’s ban on possession in places of worship for persons “tasked” with protection of these places. The Supreme Court has allowed the Second Circuit’s stay to remain in place pending a merits decision, but Justices Alito and Thomas cautioned in a separate statement that the Supreme Court’s order was not on the merits. Rather, it was entered simply to allow the Second Circuit to manage its docket. See Antonyuk v. Nigrelli, 143 S.Ct. 481 (2023) (Mem). These two Justices likewise noted that “[t]he New York law at issue in this application presents novel and serious questions under both the First and the Second Amendments.” Id. A similar order denying a stay was issued by the Supreme Court in Gazzola v. Hochul, --- F.Supp.3d ----2022 WL 17485810 (N.D.N.Y. 2022), a case involving claims by firearms dealers challenging several different New York laws under a variety of claims. See Gazzola v. Hochul, 2023 WL 221511 (S.Ct. Jan. 18, 2023) (denying an application for a stay).

It is thus fair to say that these issues are already on the Supreme Court’s radar. Indeed, Justices Alito and Thomas invited the Antonyuk plaintiffs to again seek relief from the Supreme Court “if the Second Circuit does not, within a reasonable time, provide an explanation for its stay order or expedite consideration of the appeal.” 143 S.Ct. at 481. As a result, the Second Circuit quickly expedited these cases and has scheduled oral argument for March 20, 2023, in all five of these appeals (Antonyuk, Christian, Hardaway, Spencer and Gazzola). No appeal has been filed in Koons and Siegel (TRO orders are generally not appealable). We expect a preliminary injunction to be issued soon in both cases. New Jersey may then elect to appeal such an order to the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1).

Bruen Holdings: The Bruen Court ruled that “the standard for applying the Second Amendment is as follows: When the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” 142 S.Ct. at 2127. The relevant time period for that historical analogue is 1791, when the Bill of Rights was adopted. 142 S.Ct. at 2135. That is because “‘Constitutional rights are enshrined with the scope they were understood to have when the people adopted them.’” Id., quoting District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 634–635 (2008). As stated in Hirschfeld v. Bureau of Alcohol, Firearms, Tobacco & Explosives, 5 F.4th 407, 417 (4th Cir.), vacated as moot, 14 F.4th 322 (4th Cir. 2021), cert. denied, 142 S.Ct. 1447 (2022), “[w]hen evaluating the original understanding of the Second Amendment, 1791—the year of ratification—is ‘the critical year for determining the amendment's historical meaning.” 5 F.4th at 419, quoting Moore v. Madigan, 702 F.3d 933, 935 (7th Cir. 2012) (citing McDonald, 561 U.S. at 765 & n.14). Thus, “’how the Second Amendment was interpreted from immediately after its ratification through the end of the 19th century” represented a “critical tool of constitutional interpretation.’” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2136, quoting Heller, 554 U.S. at 605. The Court stressed, however, that “to the extent later history contradicts what the text says, the text controls.” Id. at 2137. Similarly, “because post-Civil War discussions” of the right to keep and bear arms “took place 75 years after the ratification of the Second Amendment, they do not provide as much insight into its original meaning as earlier sources.’” Id., at 2137, quoting Heller, 554 U.S. at 614 (emphasis added).

Under Bruen, the historical analogue necessary to justify a regulation must also be “a well-established and representative historical analogue,” not outliers. Id. at 2133. Thus, historical “outlier” requirements of a few jurisdictions or of the Territories are to be disregarded. Id. at 2133, 2153, 2147 n.22 & 2156. Such outliers do not overcome what the Court called “the overwhelming evidence of an otherwise enduring American tradition permitting public carry.” 142 S.Ct. at 2154. Laws enacted in “the latter half of the 17th century” are “particularly instructive.” Id. at 2142. In contrast, the Court considered that laws in enacted in the Territories were not “instructive.” Id. at 2154. Similarly, the Court disregarded “20th century historical evidence” as coming too late to be useful. Id. at 2154 n.28.

Under that standard articulated in Bruen, “the government may not simply posit that the regulation promotes an important interest.” 142 S.Ct. at 2126. Likewise, Bruen expressly rejected deference “to the determinations of legislatures.” Id. at 2131. Bruen thus abrogates the two-step, “means-end,” “interest balancing” test that the courts had previously used to sustain gun bans. 142 S.Ct. at 2126. Those prior decisions are no longer good law. So, the constitutionality of SB 1, and SB 118 will turn exclusively on an historical analysis, as Heller and Bruen make clear that the term “keep and bear arms” in the text of the Second Amendment necessarily includes the right to possess (“keep”) and the right to carry (“bear”).

Bruen also holds that governments may regulate the public possession of firearms at five very specific locations, viz., “legislative assemblies, polling places, and courthouses,” “in” schools and “in” government buildings. Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2133, citing Heller, 554 U.S. at 599. These five all are historically justified and share the common feature that all are discrete locations that are easily identifiable. These locations are also places where armed security may be provided by the government, thus making it unnecessary for an individual to be armed for self-defense. Bruen states that “courts can use analogies to those historical regulations of ‘sensitive places’ to determine that modern regulations prohibiting the carry of firearms in new and analogous sensitive places are constitutionally permissible.” (Id.).

Again, this historical inquiry focuses on the Founding era. Thus, in Bruen, the Court rejected New York’s reliance on “a handful of late-19th-century jurisdictions,” stating these laws did not demonstrate a tradition of broadly prohibiting the public carry of commonly used firearms for self-defense.” 142 S.Ct. at 2138. The Court rejected New York’s reliance as well on other post-1791 statutory prohibitions, holding that “the history reveals a consensus that States could not ban public carry altogether.” 142 S.Ct. at 2146 (emphasis the Court’s). Thus, the State is not free to enact “sensitive area” legislation that that “would in effect exempt cities from the Second Amendment” because such laws “would eviscerate the general right to publicly carry arms for self-defense.” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2134. See Koons, 2023 WL 128882 at *12 (holding that “‘sensitive place’ is a term within the Second Amendment context that should not be defined expansively”).

In order to be a well-established, representative historical analogue, the historical law must be “relevantly similar” to the modern law (Id. at 2132). Bruen makes clear that this analogue inquiry is controlled by two “metrics,” viz., “how and why the regulations burden a law-abiding citizen’s right to armed self-defense.” Id. at 2133 (emphasis added). The inquiry is “whether modern and historical regulations impose a comparable burden on the right of armed self-defense.” Id. at 2133 (emphasis added). The Court thus ruled that “whether modern and historical regulations impose a comparable burden on the right of armed self-defense and whether that burden is comparably justified are ‘central’ considerations when engaging in an analogical inquiry.” (Id.) (emphasis added). See Koons, slip. op. at *15-*16. This focus on self-defense rules out, for example, any reliance on historical statutes that were “anti-poaching laws.” Antoynuk, 2022 WL 16744700, at *79-81. That is because such laws were not intended to restrict the right of self-defense, they were intended to protect game and the property owner’s right to hunt game on his own land. Those rights of owners are well recognized. For example, current Maryland law provides that owners and their families are not required to obtain a hunting license to hunt on the owner’s farmland, MD Code, Natural Resources, § 10-301, and owners are allowed to bar access to their land by others simply by marking their property. MD Code, Natural Resources, § 10-411.

The Bruen Court remarked that the analogue inquiry might be different where the regulation was prompted by some “unprecedented societal concerns or dramatic technological changes” id. at 2132, these Bills do not purport to identify any such matters. Gun violence is hardly new or “unprecedented.” The bans imposed by these Bills apply to all firearms and thus do not involve any “dramatic technological change.” Thus, the analysis is “straightforward” and controlled by “the lack of a distinctly similar historical regulation.” Id. Again, a State may not enact “sensitive places” legislation that that is so broad that it “would eviscerate the general right to publicly carry arms for self-defense.” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2134 (emphasis added).

Nothing in Bruen can be read to allow a State to establish any “buffer zone” around such sensitive places, such as the 100-foot zone created around all places of “public accommodation” by SB 1. Such a broad ban on carry would cover sidewalks and could easily extend into the street and thus effectively ban public carry in virtually all urban areas and many rural areas. Such a ban would plainly violate the holding in Bruen that the Second Amendment protects a broad, “general right” to carry in public, including in cities. For example, Bruen rejected New York’s attempt to justify its “good cause” requirement as a “sensitive place” regulation, holding that a government may not ban guns where people may “congregate” or assemble. 142 S.Ct. at 2133-34. The Court held that such a ban on places where people typically congregate “defines the category of ‘sensitive places’ far too broadly” and, if allowed, “would eviscerate the general right to publicly carry arms for self-defense.” Id. at 2134. These Bills effectively “eviscerate” that general right to carry by banning possession by a permit holder on any property “of another” and at or within 100 feet of any place of “public accommodation” (regardless of permission of the owner) and on or in any property “controlled” by any government entity. Under these Bills, there is hardly any public place where carry is permitted. The Bills would thus effectively “eviscerate” the general right to carry recognized in Bruen.

Bruen ruled that the State may ban guns “in” a “government building,” but the Court did not thereby bless gun bans on any “property” that a government might merely “control.” Bans in or on government-controlled property would sweep far too broadly. It would, for example, include vast tracts of State Forest lands and parks and other places where there is no historical support for such bans. See, e.g., Bridgeville Rifle & Pistol Club, Ltd. v. Small, 176 A.3d 632, 652 (Del. 2017) (holding that State parks and forests were not “sensitive places” and that Delaware’s regulation broadly banning firearms in such places was unconstitutional under Delaware’s version of the Second Amendment”); Ezell v. City of Chicago, 846 F.3d 888, 894-95 (7th Cir. 2017) (holding that Chicago’s zoning restrictions for firing ranges could not be justified as a restriction on sensitive places); Solomon v. Cook County Board of Commissioners, 550 F. Supp.3d 675, 690-96 (N.D. Ill. 2021) (invalidating a county ban on carry in parks); Morris v. Army Corps of Engineers, 60 F. Supp. 3d 1120 (D. Idaho 2014), appeal dismissed, 2017 WL 11676289 (9th Cir. 2017) (rejecting the government’s argument that Corps’ outdoor recreation sites were sensitive places).

The term “government building” as used in Bruen also plainly implies that “government” functions are performed in the building and thus that the building is secured accordingly. Such government functions do not include proprietary interests, such as mere ownership or control. As noted, Bruen made clear that a government may not ban guns in any place where people may “congregate” or assemble, and that rule does not turn on ownership. 142 S.Ct. at 2133-34 (holding that such a ban on places where people typically congregate “defines the category of ‘sensitive places’ far too broadly”). Indeed, there is a model for a proper regulation on government property, found in 18 U.S.C. § 930. That law bans firearms in “federal facilities” where such possession is done “knowingly.” 18 U.S.C. § 930(a),(b). See Rehaif v. United States, 139 S. Ct. 2191, 2196 (2019) (discussing the meaning of a “knowing” violation). Whether an act is done “knowingly” is determined by the trier of fact based on the circumstances presented in the case.

Section 930 does not create any “presumption” that any possession is done “knowingly.” Indeed, the Bill 118’s “rebuttable presumption” that a person “knowingly” possesses a firearm on the private property of another or on government “controlled” property is of dubious constitutionality. See Leary v. United States, 395 U.S. 6, 36-38 (1969) (striking down a statutory presumption and holding “that a criminal statutory presumption must be regarded as ‘irrational’ or ‘arbitrary,’ and hence unconstitutional, unless it can at least be said with substantial assurance that the presumed fact is more likely than not to flow from the proved fact on which it is made to depend”). Stated simply, it is “not more likely than not” that any person would know the meaning of the term “property controlled” by a government, much less the boundaries of all such property and thus cannot be presumed to knowingly violate this prohibition. Private property lines are often likewise indistinct or lacking in notice.

Such actual notice is critically important to compliance. For example, Section 930 specifically provides that “[n]otice of the provisions of subsections (a) and (b) shall be posted conspicuously at each public entrance to each Federal facility,” and that “no person shall be convicted … if such notice is not so posted at such facility, unless such person had actual notice” of this law. 18 U.S.C. § 930(h) (emphasis added). Finally, Section 930 narrowly defines “federal facility” to mean “a building or part thereof owned or leased by the Federal Government, where Federal employees are regularly present for the purpose of performing their official duties.” 18 U.S.C. § 930(g)(1) (emphasis added). This federal ban also applies only to possession “in” a federal facility and thus does not impose any “buffer zone.” In other words, a federal facility is not covered by this provision unless federal employees are “regularly” present in that building for work. Section 930 passes muster under Bruen. A ban on all property controlled by a government does not.

Remarkably, SB 118 also presumes to regulate possession on all property controlled by the federal government. There are many tracts of property over which the federal government constitutionally exercises exclusive jurisdiction. See U.S. Const. Article I, § 8, cl. 17; 18 U.S.C. § 7. Stated simply, the State has no jurisdiction to regulate at all in such areas. Examples of such exclusive jurisdiction areas include military installations, federal buildings, post offices, and some high-value or security-sensitive sites, all of which are abundant in Maryland. SB 118 is thus flatly unconstitutional under Article I, § 8, cl. 17, to the extent it purports to ban firearms on all property “controlled” by the federal government. Exclusive means just that, exclusive.

To be sure, federal law may incorporate State laws by reference as to lands over which there is concurrent jurisdiction (but not as to exclusive jurisdiction areas). See Assimilative Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. § 13 (“ACA”). Such “assimilated” crimes are enforced by federal law enforcement and are tried in federal court. But even then, such incorporation may not occur if the State law is contrary to federal policy. See, e.g., United States v. Kelly, 989 F.2d 162, 164 (4th Cir.), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 114 (1993) (“federal courts have consistently declined to assimilate provisions of state law through the ACA if the state law provision would conflict with federal policy”). For example, federal policy specifically addresses possession in the National Park System. Pub. Law 113-287, § 3, 128 Stat. 3168 (2014), codified at 54 U.S.C. § 104906. That legislation provides that “[f]ederal laws should make it clear that the 2d amendment rights of an individual at a System unit should not be infringed,” 54 U.S.C. § 104906(a)(7). Permit holders throughout the United States thus may carry in the National Park System. SB 118 would flatly ban such carry and is thus contrary to federal policy.

The “Critical Year” Under Bruen Is 1791: Again, the relevant date for historical analogues is 1791, when the Bill of Rights was adopted. See Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2136 (“when it comes to interpreting the Constitution, not all history is created equal. Constitutional rights are enshrined with the scope they were understood to have when the people adopted them.”). Thus, the Supreme Court has “generally assumed that the scope of the protection applicable to the Federal Government and States is pegged to the public understanding of the right when the Bill of Rights was adopted in 1791.” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2137. Bruen thus looked primarily to 1791 in conducting its historical analysis. Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2144-46. The Court also examined and rejected New York’s reliance on post-Civil War history, stating “because post-Civil War discussions of the right to keep and bear arms ‘took place 75 years after the ratification of the Second Amendment, they do not provide as much insight into its original meaning as earlier sources.’” 142 S.Ct. at 2137, quoting District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 614 (2008). The appropriate line is thus the Civil War, the late 19th century. As noted, Territorial laws and laws enacted in the 20th century may not be considered.

That line is fully consistent with the Court’s reliance on the “relatively few 18th- and 19th-century” laws in identifying the five sensitive places found by the Court. 142 S.Ct. at 2133. Given the Court’s reluctance to rely on post-Civil War laws, that reference to “relatively few 18th- and 19th-century” laws can only be reasonably understood to refer to laws in the 1700s and early 1800s. Indeed, the Court cautioned “against giving post-enactment history more weight than it can rightly bear.” 142 S.Ct. at 2136. Thus, as Justice Barrett noted in concurrence, “today’s decision should not be understood to endorse freewheeling reliance on historical practice from the mid-to-late 19th century to establish the original meaning of the Bill of Rights.” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2163 (Barrett, J., concurring). In short, 1868 is of minor importance in the analogue analysis. See NRA v. BATFE, 714 F.3d 334, 339 n.5 (5th Cir. 2013) (Jones, E., J. dissenting from the denial of rehearing en banc and joined by six other circuit judges) (“Heller makes plain that 19th-century sources may be relevant to the extent they illuminate the Second Amendment’s original meaning, but they cannot be used to construe the Second Amendment in a way that is inconsistent with that meaning”);

Importantly, the Second Amendment cannot mean one thing for the States and another thing for the federal government. Any such suggestion was squarely rejected in McDonald v. City of Chicago, 561 U.S. 742, 783-84 (2010). There, the Court held that “if a Bill of Rights guarantee is fundamental from an American perspective, then . . . that guarantee is fully binding on the States.” Bruen held that “individual rights enumerated in the Bill of Rights and made applicable against the States through the Fourteenth Amendment have the same scope as against the Federal Government.” 142 S.Ct. at 2137. Thus, cases involving federal restrictions are directly precedential in cases involving State restrictions.

The McDonald Court found that Second Amendment rights were “fundamental to our scheme of ordered liberty and system of justice.” McDonald, 561 U.S. at 764. Nothing in that analysis speaks to “investing” 1791 rights with “new 1868 meaning” or the intent of the “people” in 1868. Quite to the contrary, the right was “fundamental” because “[s]elf-defense is a basic right, recognized by many legal systems from ancient times to the present day.” Id. The incorporation of the Second Amendment into the 14th Amendment is by operation of law; it does not rely on any legal fiction that the “people” desired to incorporate the Bill of Rights when the 14th Amendment was adopted. The incorporation doctrine emerged long after 1868, as McDonald makes clear. 561 U.S. at 759-60.

Bruen relies on two very recent decisions, Ramos v. Louisiana, 140 S.Ct. 1390 (2020), and Timbs v. Indiana, 139 S.Ct. 682 (2019), in holding that the Bill of Rights is the same for both the federal government and the States. Ramos held that the Sixth Amendment right to a unanimous jury verdict was incorporated against the States and overruled prior precedent that had allowed the States to adopt a different rule under a “dual track” approach to incorporation. In so holding, the Court relied on 1791 as the relevant historical benchmark. Ramos, 140 S.Ct. at 1396. Similarly, in Timbs, the Court held that the Excessive Fines provision of the Eighth Amendment was incorporated as against the States. Timbs, 139 S.Ct. at 686-87. In so holding, the Court once again looked to the scope of the right as it existed in 1791. Id. at 688. The Timbs Court found that this scope was simply confirmed by “an even broader consensus” in 1868. Id. Ramos and Timbs make clear that 1791 is the controlling inquiry and that later understandings may be viewed as confirmation, not changing the right itself. In all cases, the text is controlling over history. Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2137 (“the extent later history contradicts what the text says, the text controls”) (citation omitted). The text of the Second Amendment thus controls over history and that text did not change in 1868.

No court, including the pre-Bruen State law cases, has suggested that the 1868 meaning applies to the federal government. The few cases involving State laws looked to 1868 without examining whether 1868 is controlling as to the federal government. Those prior decisions pre-date not only Bruen, but came before Ramos and Timbs, where the Court made clear that the Bill of Rights mean the same thing for both the federal government and the States. While the Third Circuit’s 2021 decision in Drummond v. Robinson Township, 9 F.4th 217, 227 (3d Cir. 2021), made a reference to “the Second and Fourteenth Amendments’ ratifiers,” it did not address, much less resolve, the question of whether the 1868 meaning is controlling, even as to State laws. It certainly did not suggest that 1868 was controlling for federal laws. Indeed, if 1868 is controlling there would have no point to the court’s reliance on Second Amendment “ratifiers.” Likewise, Gould v. Morgan, 907 F.3d 659, 669 (1st Cir. 2018), never addressed whether the 1868 meaning was controlling for the federal government.

In Hirschfeld v. BATF, 5 F.4th 407, 417 (4th Cir.), vacated as moot, 14 F.4th 322 (4th Cir. 2021), cert. denied, 142 S.Ct. 1447 (2022). (decided in 2021), the Fourth Circuit held that “[w]hen evaluating the original understanding of the Second Amendment, 1791—the year of ratification—is ‘the critical year for determining the amendment’s historical meaning.’” Id. at 419. In so holding, Hirschfeld quotes and relies on Moore v. Madigan, 702 F.3d 933, 935 (7th Cir. 2012), where the Seventh Circuit looked to 1791 as the “critical” period in invalidating a State law (Illinois) that had restricted the right to the home. Hirschfeld and Moore are not alone in looking to 1791. See United States v. Rowson, 2023 WL 431037 at *22 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 26, 2023) (“Viewing these laws in combination, the above historical laws bespeak a ‘public understanding of the [Second Amendment] right’ in the period leading up to 1791 as permitting the denial of access to firearms to categories of persons based on their perceived dangerousness.”); United States v. Connelly, 2022 WL 17829158 at *2 *n.5 (W.D. Tex. Dec. 21, 2022) (rejecting the government’s reliance on “several historical analogues from ‘the era following ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868’”); United States v. Stambaugh, --- F.Supp.3d ---, 2022 WL 16936043 at *2 (W.D. Okl. Nov. 14, 2022) (“And since ‘[c]onstitutional rights are enshrined with the scope they were understood to have when the people adopted them,’ the government must identify a historical analogue in existence near the time the Second Amendment was adopted in 1791.”) (citation omitted); United States v. Price, --- F.Supp.3d ----, 2022 WL 6968457 at *1 (S.D. W.Va, Oct. 12, 2022) (“Because the Second Amendment was adopted in 1791, only those regulations that would have been considered constitutional then can be constitutional now.”).

Hirschfeld involved a federal statute (the ban on sales of handguns to 18-20-year-olds codified at 18 U.S.C. § 922(b)(1)), but the court’s holding that 1791 was the “critical” period and its reliance on Moore is plainly at war with any notion that the 1868 meaning controls the scope of the right for either the federal government or the States. The General Assembly should follow Hirschfeld.

Outlier History Must Be Disregarded: As noted above, Bruen holds that the text and history of the Second Amendment establish a “general right” to public carry subject only to the five exceptions specified by the Court, viz., schools, government buildings, polling places, legislative assemblies and courthouses. While Bruen did not rule out other locations, the Court made clear that the burden is on the government to justify additional locations by reference to Founding era laws that were “relevantly similar” and “comparable” under the two metrics specified by the Court. See Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2132-34. Those two metrics are “how and why the regulations burden a law-abiding citizen's right to armed self-defense.” Id. at 2133. Historical laws that did not or were not intended to burden that right in comparable ways are simply not analogues. Such “[a]nalogical reasoning requires judges to apply faithfully the balance struck by the founding generation to modern circumstances.” Bruen, 142 S.Ct. at 2133 n.7. That approach “is not an invitation to revise” “the balance struck by the founding generation” “through means-end scrutiny.” Id.

Any attempt to abrogate Bruen’s recognition of a “general right” to carry in public through the imposition of a multitude of locations and/or or exclusion zones cannot possibly be justified. Bruen holds that courts should not “uphold every modern law that remotely resembles a historical analogue,” because doing so “risk[s] endorsing outliers that our ancestors would never have accepted.” 142 S.Ct. at 2133 (citation omitted). That point is particularly applicable to legislative schemes, like New York’s and New Jersey’s, that effectively sought to do away with the “general right” to carry in public. Our “ancestors” would have “never accepted” such a law. That the New York and New Jersey laws have been enjoined is thus not surprising. Any attempt to enact similarly broad bans on the general right to carry in public will meet the same fate.